Haidt must have read an awful lot of philosophy, you might think, to gather the evidence for such a large generalisation, or alternatively he may not have read any at all, but in any case he summed up his discovery in one of his celebrated metaphors.The mind, he said, is not a peaceful philosophical realm where reason and consciousness reign, but a battlefield of conflicting impulses largely beyond our knowledge and control: or rather, it is like a mighty elephant crashing through the forest with a would-be rational rider perched precariously on its back. They were “filled with cognition”, and the ancient prejudice against them was no more than a professional myth – a conspiracy designed to “make philosophers look pretty darned good”, and “justify their perpetual employment as the high priests of reason”. But recent work in cultural psychology showed that the philosophers had got it wrong: emotions were not stupid distractions from truth, but indispensable forms of perception. He is also, it would seem, one of the great communicators, with an easy way with words and a gift for grand, memorable metaphors.Ī few years ago, in a book called The Happiness Hypothesis, Haidt focused on the role of emotions in human life, hoping to rescue them from the dogmatic disdain of Western philosophers who, so he said, have been “worshipping reason and distrusting the passions for thousands of years”.

He is an enthusiastic public advocate for his discipline, with streams of anecdotes about all those wonderful people – teachers, colleagues, friends, students, parents, wife and kids – without whom he would not have been able to rise to the top of his game.

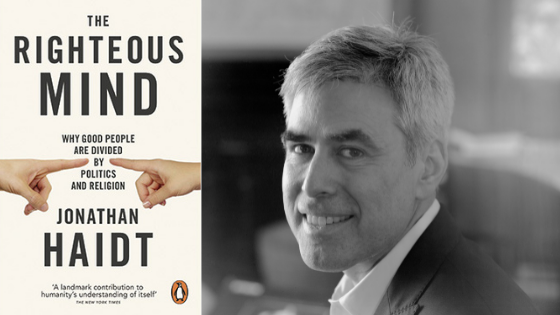

Cultural psychology applies the principles of Darwinian natural selection to problems about morality, consciousness and human existence, and Haidt believes that it offers definitive evidence-based solutions to the problems that have been baffling philosophers since the dawn of civilisation. Jonathan Haidt is a world leader in the new discipline of cultural psychology, which combines the psychologist’s understanding of what goes on inside our heads with the anthropologist’s interest in the social meanings that surround us. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion by Jonathan Haidt (Allen Lane)

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)